Welcome to Small Wins, a newsletter that shares a small win with you every other week — one that has the power to improve your cooking, your home, your life. If you’ve found your way over here but are not yet subscribed, here, let me help you with that:

For years I assumed that the duck confit served in bistros across Paris was somehow complicated — something to be reserved for the professionals. Uh, no: quite the opposite. Duck confit, it turns out, is a slow cook requiring just THREE ingredients (one of which is the salt!), a low oven temperature and some time.

A delicious dish to have at any time, duck confit comes into its own when you want to cater a relaxed dinner party. Two reasons: (1) the oven does most of the work for you and (2) it can be cooked the weekend before (yes, really) and then briefly roasted on the night to heat it through and crisp up the skin. It’s ludicrously straightforward.

Even better: the joys of this technique are not just relegated to duck — confit is fantastic employed with other meats (chicken, turkey legs) as well as pulses (chickpeas) and vegetables (tomatoes! garlic! leeks!). It really ought to become a part of every home cook’s repertoire.

Love,

Alexina

Coming up on Small Wins — A simple formula for soup, the best hot chocolate in the world + the secret to excellent roast potatoes

For my Small Wins+ community — This month it’s all about potatoes and next month I’m tackling the essentials relating to chicken! We’ll cover how to break down a chicken and why it will save you $$, the Chinese restaurant secret to tenderising meat, the only way to treat a chicken breast, the technique that’s key to a perfect roast chicken and more. Become a paid subscriber to get access.

CONFIT AS A TECHNIQUE

I’ll confess: I didn’t confit until later in life.

To be truthful, the concept of confit — which is the act of poaching something in fat — didn’t initially appeal. It sounded like something that ought to be reserved for professionals. It sounded like it might get greasy.

But I’m pleased to say that that’s all behind me now because confit’ing foods — whether it’s a piece of meat or a selection of vegetables — produces an ultra-delicious, melt-in-the-mouth outcome in return for very little effort.

And when it comes to all that fat, well, there are some important qualifiers:

When cooking meat this way, it doesn’t actually absorb a huge amount of the fat (see my note further below)

High-quality animal fat, butter or extra virgin olive oil cooked at a lowish temperature is far better for you than ultra-processed fats cooked at high temperatures

The fat used to confit a food can be strained and reused for future confit, making it more sustainable that you would initially think

You would be forgiven for getting confit confused with deep-fat frying, both being techniques that require you to submerge your food in a deep vat of oil (which sounds pretty alarming, I’ll admit). But the key difference — as in a lot of cooking — is temperature (as well as the type of fat itself, which is dictated by said temperature).

With deep-fat frying you are taking the oil to above 160°C, which necessitates using fats with a high smoke point (typically ultra-processed). To state the obvious: it’s an aggressive form of cooking. Confit, meanwhile, is a supremely gentle cooking technique where the oil is taken to around 95°C. Since surface browning only starts to happen at 110°C confit is not a technique designed to brown (although the grill can do that at a later point) — it’s really about steaming the meat from the inside out (we talked about steaming a few weeks ago!). It’s the perfect balance: the fat is hot enough to break down tough connective tissue, but not so hot that it causes significant evaporation. Needless to say, the outcomes of deep-fat frying vs confit are night and day: the former is all about crispiness and browning; the latter, melting softness.

You’ll fall in love with confit for its simplicity: throw everything into a pan, pop it into the oven and leave it to its own devices (and you to yours). But the process of confit’ing an ingredient is also a shortcut to deliciousness because fat contributes flavour in two ways:

Fat itself contains flavour because it repels water, and water, in turn, repels many aromatic molecules. Something I learnt from Samin Nosrat is that an animal’s fat will taste more distinctly of that animal than its lean mean — and this makes sense if you think of a chicken: the leg meat tastes more chicken-y than the breast because it has a higher fat content.

Fat is also a carrier of flavour since fat molecules coat the tongue, holding aromatic compounds in contact with your tastebuds.

But whilst confit is a gorgeous and flavourful way to cook meat and other ingredients it is, above all, a preservation technique. For bacteria to thrive they need air and no air can penetrate fat: ergo anything submerged in fat is largely inhospitable to bacteria. This means that confit’d meat can legitimately be stored in its fat outside of the fridge for weeks and months!

The term confit comes from the French verb confire which means to preserve, and was first applied in Medieval times to any food preserved through slow cooking in a liquid: fruits, for example, would be confit’d in a concentrated sugar syrup. Over time it has come to be most closely associated with cooking meat and is inextricably linked with French cuisine — the region of Occitan, where goose fat is used for cooking, is known as “confit country”. Traditionally, confit duck or goose would be stored and aged for months, but that doesn’t happen much nowadays.

For those interested in cheffy cooking techniques, it’s worth noting that, in many ways, the technique of confit is probably the closest you can get to a sous vide effect (without a sous vide machine). Though sous-viding doesn’t require fat, its most distinctive quality as a technique is that it maintains an even temperature throughout cooking. The act of confit’ing does the same.

An alarming amount of fat

You should know that meat doesn’t absorb that much fat when confit’d. I measured the butter before and after making the duck confit below, and each duck leg had absorbed around a tablespoon — the majority of the butter was left behind.

The leftover butter/fat can be strained through a muslin cloth and re-used for future duck confit — see details in the method below. It’s also great for roasting potatoes, sautéing vegetables or making delicious shortcrust pastry for a savoury bake.

CONFIT DUCK

Adapted from my cookbook, Bitter

Serves 3 to 4

For an everyday meal I like to serve this with buttermilk mashed potatoes (see the recipe in potatoes 101) — or for a dinner party, these brothy white beans that I developed for my guest post on

’s Substack The Dinner Party.If you like, you can salt the duck legs the day before you confit them — this is best practice if you’re planning on storing the confit out of the fridge or for a long time. It will also offer a slightly tastier result. It’s not essential, however, and I’ve made this plenty of times without carrying out that additional step.

Finally, you should also know that shredded duck confit makes an excellent ragu.

For the confit duck

4 duck legs, skin on

3/4 tbsp flaky sea salt (I use Maldon)

500g unsalted butter, cut into thick slices — you could cut this with 50% duck or chicken fat if you like

You can also add some aromatics to the oil, for example 1 tbsp slightly crushed coriander seeds and/or some hard herbs (e.g. bay leaves, thyme etc.).

Equipment

A heavy-bottomed casserole dish that can fit the duck legs in a single layer (ideally)

Method

Preheat the oven to 120°C fan/140°C/275°F/gas 1.

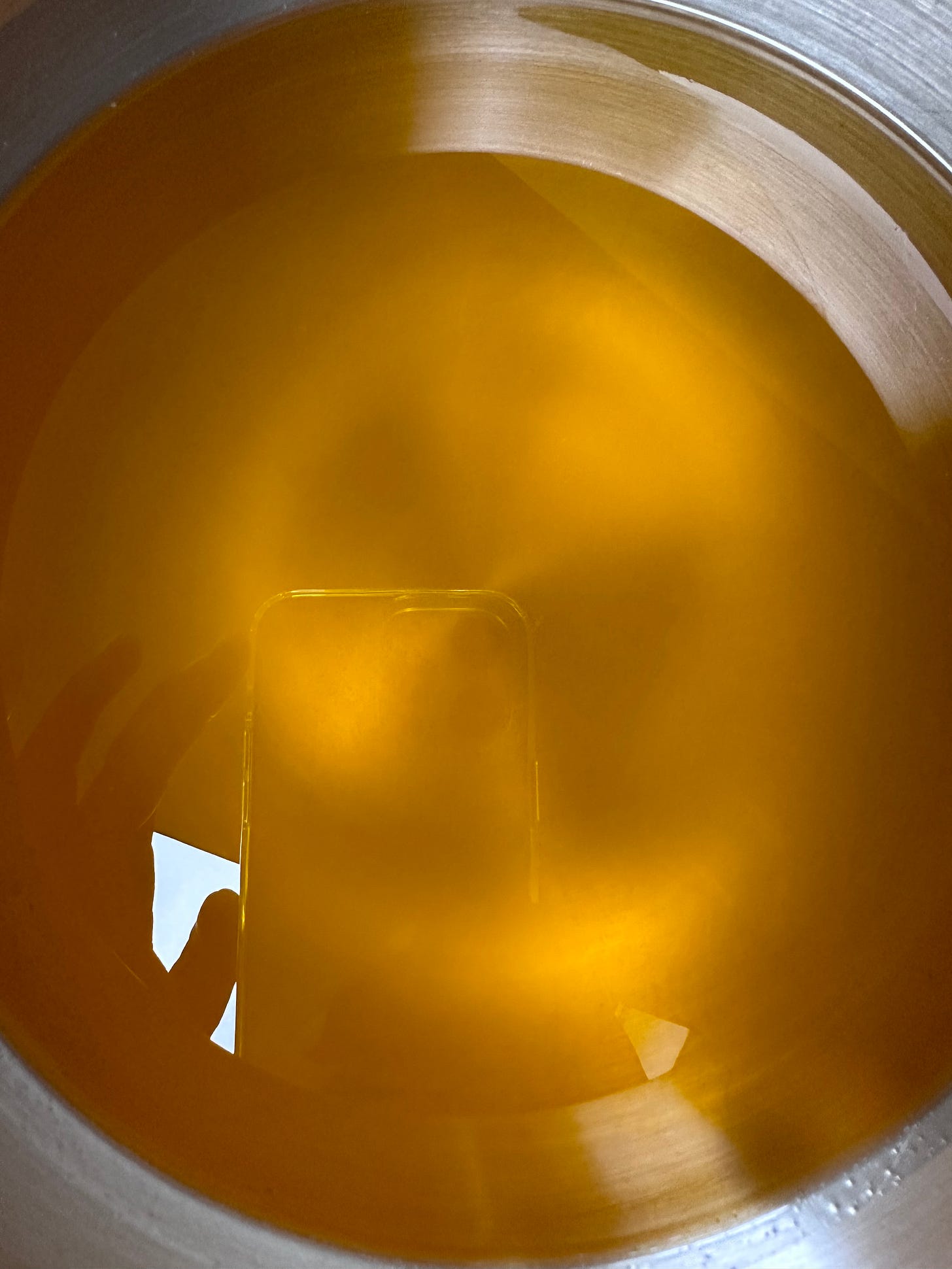

Season the duck legs evenly with the flaky sea salt, then place in a cast-iron casserole (Dutch oven) or ovenproof dish that fits them snugly in a single(ish) layer. Cover with the butter then wrap the dish tightly with a couple of sheets of kitchen foil and bake for 2 1/2 to 3 hours.

Remove from the oven and allow to cool for 5–10 minutes (see notes below if you’re making the confit duck ahead). Transfer the duck legs to a plate, leave the fat in the dish to cool for a further 5–10 minutes, then strain through a sieve (fine mesh strainer) and transfer to an airtight storage container. This fat can be stored in the fridge for up to 3 months and re-used to make more duck confit.

Preheat the oven to 220°C fan/240°C/475°F/gas 9, open the windows and boil the kettle. Place the confit duck legs, skin-side up, on a rack set over a roasting tin. Pour 2cm (3/4in) boiling water into the roasting tin and place in the oven for 20–25 minutes until the skin is crispy and a deep golden brown all over.

Make-ahead: The confit duck can be made a week ahead (or longer tbh, which does make it even more delicious… but you probably don’t want to clutter up your fridge). Allow it to cool then store the duck legs in a sealed container in the fridge, making sure that they are completely submerged in the fat. On the day you want to cook them, remove the container from the fridge and allow the duck legs to come to room temperature. Prise the duck legs out of the fat and proceed per the recipe.

FURTHER READING + RESOURCES

To read more about the wonders of fat in cooking, it’s worth getting a copy of Samin Nosrat’s classic Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat.

Here are some other things you should confit: garlic, chickpeas, leeks, turkey legs, tomatoes and carnitas.

If you’re looking to buy organic animal fat, Borough Broth do a range that includes chicken, beef and pork fat.

Nice, never thought to cook a duck confit at home either, super easy, no wonder it is popular in restaurants x