Small Win #19: Before forced rhubarb season ends, make this

Pretty in pink! Plus the merits of maceration via Georgian winemaking

Welcome to Small Wins, a newsletter that shares a small win with you every other week — one that has the power to improve your cooking, your home, your life. If you’ve found your way to this newsletter but are not yet subscribed, here, let me help you with that:

If you follow a lot of foodie creators here on Substack or over on Instagram then perfectly pink forced rhubarb will have been popping up all over your feeds the last few weeks, with countless recipes to choose from.

I’m sure all of those recipes are gorgeous — in fact it would be remiss of me to not shout out

’s gorgeous ‘rhubarbmisu’ — but if I had to commit just the one rhubarb recipe to memory, it would be today’s small win: this rhubarb compote slash ‘quick jam’.Not only does this recipe capture the essence of rhubarb most purely, and not only is it very quick and easy, but it’s also one of those really useful ‘component’ recipes that can be used in all sorts of ways: with yoghurt and granola or on top of porridge for breakfast; as a filling for a seasonal Victoria Sponge; as the side piece to a baked cheesecake or wobbly panna cotta; as a pop of colour against a comforting pud (rice pudding, bread & butter pudding — it still feels cold enough to mention these); or even as a small gift for a friend or neighbour. Many things.

Consider this your cue, then, to pick up some of the pink stuff on your next trip to the shops and add this ‘quick jam’ to your cooking repertoire — it’s delicious, adaptable and versatile.

Love,

Alexina

Coming up on Small Wins — The best cake to make with kids (no scales!). The easiest, quickest bread in the world. An excellent way to cook any white fish fillet.

For my Small Wins+ community — I’m currently building an ingredients substitutions tool as part of an Extra Win that I’ll be sharing in the next few weeks. It’s going to be all about the art of following a recipe (i.e. what to follow vs what can you play around with, and how to make recipes work for where/who you are and what’s available to you at that precise point in time). Slightly further ahead, April’s deep-dive will be on the savoury side of eggs! From the best boiled eggs and soldiers to foolproof mayonnaise, all the essentials will be covered. Become a paid subscriber to gain access.

PRETTY IN PINK (WHAT IS FORCED RHUBARB?)

‘Normal’ rhubarb and forced rhubarb aren’t different varieties, they’re simply grown differently: the stalks of unforced rhubarb push northwards into plain air and sunlight, whilst the forced stuff is grown in the dark.

Plants need light to photosynthesise and produce chlorophyll, which in turn makes them green (thank you GCSE biology). Exclude every last shard of light, however, and this process is arrested. It sounds almost cruel but by keeping rhubarb in the dark it is forced to reach out prematurely in search of light, producing smooth, pale pink stems in the process.

Rhubarb is technically a vegetable and the unforced stuff loves to remind you of this fact with its fibrous, desaturated stalks and subtly bitter flavour. Forced rhubarb, on the other hand, presents pretty convincingly as a fruit: it needs less sugar to balance out its tartness, the flavour is delicate and the texture tender.

Forced rhubarb is devastatingly romantic, actually — not just because it’s the perfect pink colour but because it is handpicked by candlelight.

If you’re interested to know what that looks like, the now infamous Edinburgh bakery Lannan (which I got to sample last weekend) recently posted about their trip to Cook’s Farm in Yorkshire (fifth generation farmers of forced rhubarb!). Their carousel of photos is gorgeous and includes one of said candlelight.

Forced rhubarb: a true British treasure!

THE WONDERS OF MACERATION (A POWERFUL PROCESS!)

Maceration is a process that can elevate any fruit in return for very little effort. And whilst it has a fancy name, it’s an exceptionally simple technique — one that I remember my grandmother using with height-of-summer berries.

The Latin macerare means ‘to soften’ or ‘to steep’, so maceration essentially describes the process of allowing something to sit in a liquid for a period of time (not to be confused with marination). In the context of food, I associate it most strongly with fruit.

The simplest example of maceration is when you toss berries with a spoonful or two of sugar and place them aside for 10 to 15 minutes. Sugar is hygroscopic (it attracts water) and in this short window of time it starts to draw out the water present in the fruit. The fruit softens and becomes more concentrated, whilst the juices mix with the sugar. The result is fruit that tastes even more of itself, with a beautifully hued syrup to boot.

A good rule of thumb when macerating berries is to add 15-20% sugar

But maceration is used in bigger contexts, too: it’s the secret technique that makes Christine Ferber’s jams so legendary, it’s the chief means of producing flavoured alcohol such as liqueurs and it is foundational to the long and deep history of natural winemaking in Georgia.

The majority of wine produced today is preserved through the addition of sulphites which enables winemakers to deliver consistent and stable wines. The level of added sulphites permitted in natural, organic and biodynamic wines, meanwhile, is significantly lower*.

One of the biggest challenges that natural wine producers face is how to keep their wines stable over time (and with travel) without those higher levels of sulphites.

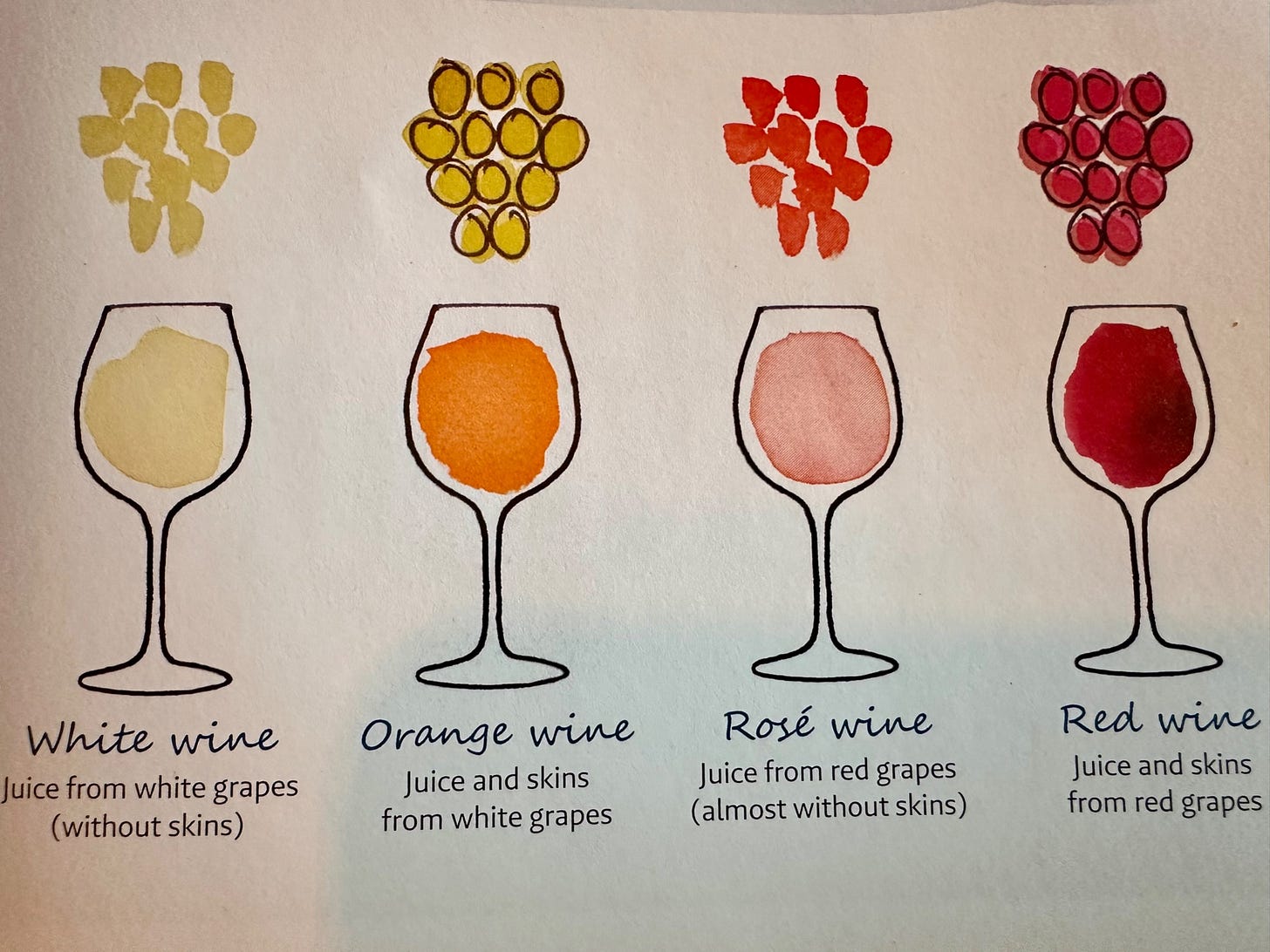

Georgia, often described as ‘the cradle of wine’, is acknowledged as one of the most important wine nations in antiquity, with a long and continuous tradition of winemaking dating back to 6,000 - 5,800 BC! And at the core of Georgian winemaking is orange wine.

Whilst orange wine may be perceived as a more recent addition to the wine space — the current cool kid of the (natural) wine scene — orange wine is actually the old guy, the OG. Because it came about as a way to produce more stable wines with white grapes.

Way before winemaking became a global commercial endeavour, winemakers in Georgia were making age-worthy orange wines that leaned on maceration to help keep them stable.

As Iago Bitarishvili, Georgian wine producer, states: “long maceration with skin and stems contact [i.e. orange wine] is naturally stable wine.” So there is real power in this process.

But back to rhubarb.

In today’s recipe we are relying on a form of maceration — albeit one hurried along by the application of heat.

A lot of recipes for compotes will have you add water or lemon juice upfront, but in this case the first step — which crucially has you cover the pot — is all about drawing out the liquid that already exists in the fruit. The result is rhubarb that cooks in its own juices which ultimately keeps it all very rhubarb-y in flavour.

*Sulphites do occur naturally in wine as a byproduct of the fermentation process.

RECIPE: A RHUBARB ‘QUICK JAM’ TO GO WITH EVERYTHING

I would describe this as halfway between a compote and a jam but, crucially, the natural tartness of the rhubarb still shines through. It’ll last for at least a couple of weeks in the fridge — often much longer.

Yields around 1 x 370ml jar of compote — this method works best with small batches. You can double the recipe if you really want, but the outcome is slightly inferior.

Ingredients:

450g (1lb) trimmed rhubarb, chopped into 2cm batons

100g (1/2 cup) caster sugar

1 tsp vanilla bean paste

Method

Add the ingredients to a small, non-reactive pan, give a gentle stir, then cover with a lid. Set over a medium-low heat and cook until the fruit’s natural juices have been released, around 5 minutes.

Remove the lid and simmer gently, giving it a stir every so often to stop it sticking to the bottom. You’re looking for the compote to start to thicken and gel slightly, around 15 minutes.

Transfer to a jar and, once cooled, store in the fridge.

Variations: I like this best with rhubarb but it works with other fruits too (e.g. strawberries, plums) — just bear in mind that they may need longer cooking at step 2, and may require a bit of skimming too.

FURTHER READING + INFO

Flavour combinations: Many combine rhubarb with orange but I find that orange can be a bit of a bully in this context. And though vanilla is so often considered pedestrian — a miscarriage of justice if ever there was one! — I find it makes a particularly perfect pairing for fruits that have a degree of tartness: rhubarb, apricots, sour cherries. Rhubarb and ginger are also harmonious together.

Hypocrisy: I know that I’ve just stated that today’s recipe is the only rhubarb one that you need, and that rhubarb and orange don’t go together, but this recipe is the one exception to both of those rules: Maria Elia’s Rhubarb, Rose & Almond Bircher Muesli from her cookbook Smashing Plates. If you’re a fan of bircher muesli and/or overnight oats, this is a real treat version. I sometimes sub the almonds for pistachios.

Guardian Feast: Keep an eye out for my savoury rhubarb recipes appearing in today’s newspaper!

Question from the 60th latitude (which is about 20 minutes' walk north of my house) : when you say that rhubarb season is ending, do you mean that you harvest rhubarb now? Because there's still a bit of snow on my rhubarb patch, even though we've had an appallingly warm and snow free winter! Or is the forced variety (which is a new one for me) grown in hothouses?