Nothing used to infuriate me more than my mum’s refusal to follow a recipe.

I simply couldn’t grasp how she could know whether Jamie Oliver’s recipes were any good without precisely following the instructions (right?!).

During the process of cooking, many things are in flux — temperature, colour, sound, smell — which is why, as a novice cook, I clung to recipes for dear life. They felt like the only sure footing within an ever-shifting process.

But the more you cook, the less enslaved you become to these written guidelines — and this is a good thing (mostly).

For one, recipes can never be foolproof because there are far too many variables involved.

And two, though we often think of recipes as objective, instructive non-fiction writing, they are still written from a specific point of view: from the lens of the author’s own cooking knowledge and their own kitchen. So a writer’s assumptions will creep into their recipes, often without them ever being aware of it.

Home cooks do well, then, to approach any recipe with a gentle level of skepticism. Even so, it is important to realise what you can vs shouldn’t change in a recipe — i.e. there are some rules. And today we’re going to chat about them.

Specifically:

How to understand an author’s style and intention

How to tweak a recipe whilst keeping in the spirit of its creation

Getting to know your own palate, and how to adjust the seasoning of a dish accordingly

How to substitute ingredients thoughtfully — including a substitutions tool that I’ve built just for you <3

Here’s what I will not be doing:

Telling you to ‘read the recipe all the way through before starting’

Or advising that you ‘prepare and weigh out all of your ingredients before cooking’

… because who even does that??

Love,

Alexina

HOW TO DISCERN THE WRITER’S INTENTION

As with most things in life, context matters.

When you’re coming to a recipe, the first thing you should consider is its creator — because that will inform your approach.

If I’m making an Ottolenghi recipe, I’m going to follow it pretty much to the letter. Why? Because when Ottolenghi tells me to use 3/4 teaspoon of sumac, I can be reasonably confident that the Ottolenghi Test Kitchen (OTK) have also tested that recipe with 1/2 teaspoon of sumac and 1 teaspoon of sumac, and concluded that 3/4 of a teaspoon is the right balance.

Granted, Ottolenghi is well known these days and many of us are familiar with his style, but you don’t have to know much about the writer to pick up when they are a detail-oriented recipe developer — you often just need to read the ingredients list.

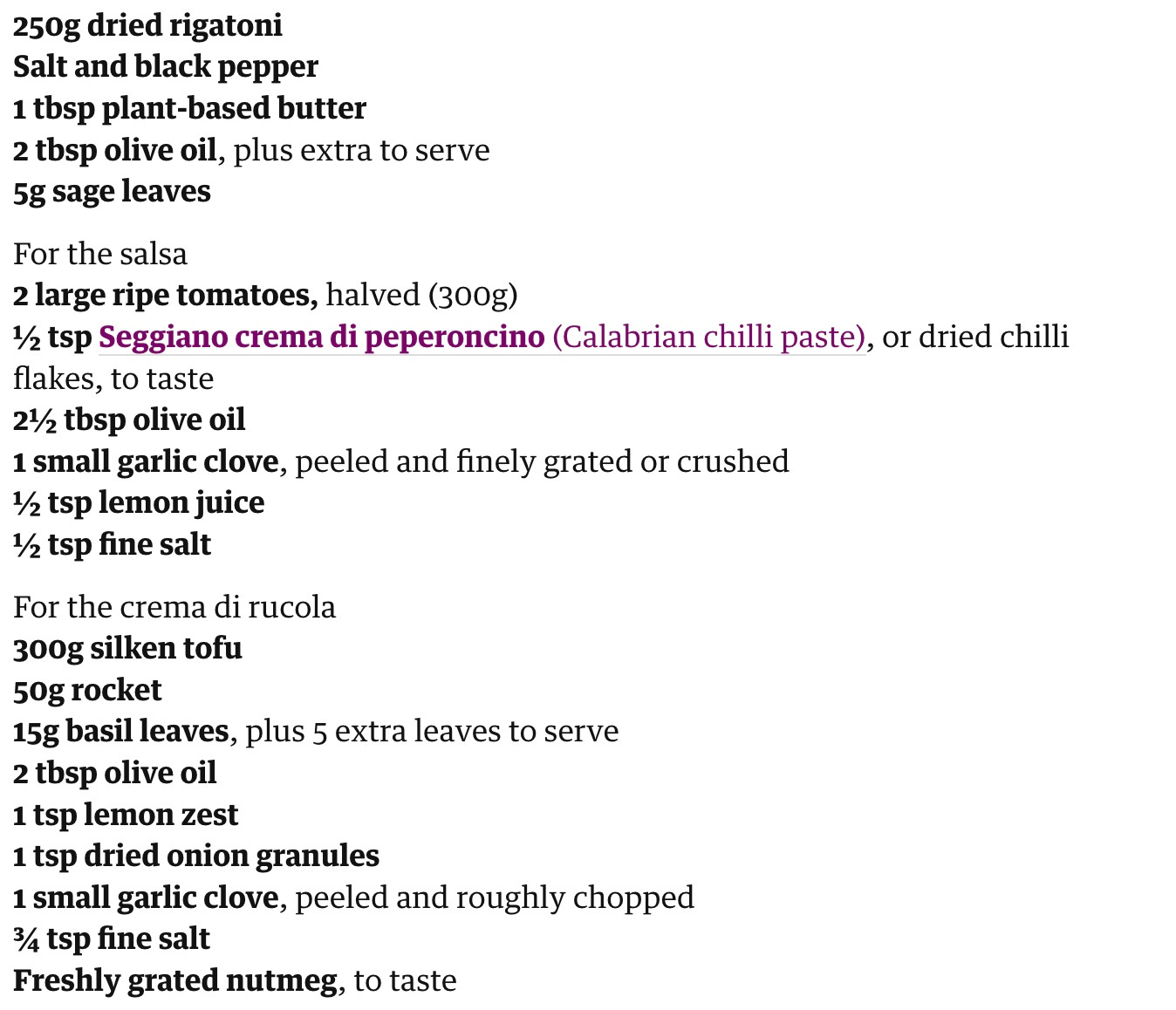

As an example, here’s a recipe that

wrote for the Guardian:There are a lot of indications in this list alone that Ixta is a precise cook:

She specifies ingredient weights at 5g increments (“5g sage leaves”, “15g basil leaves”) and 1/2 tbsp increments (e.g. “2 1/2 tbsp olive oil”) — this is a level of granularity that many recipes developers don’t go to

She doesn’t leave it at “2 large ripe tomatoes” she adds the weight in brackets

She weighs out 1/2 tsp of lemon juice rather than using a more generic description e.g. ‘a squeeze of lemon’

She specifies that you prep the garlic in the salsa differently to the garlic in the crema di rucola (finely grated vs roughly chopped)

She doesn’t just say ‘Calabarian chilli paste’, she specifies the brand used

All of the above indicates that we ought to follow the recipe carefully: Ixta has clearly been very intentional in how she has composed this recipe. And this makes sense given that one of Ixta’s primary motivations is flavour (she wrote the book on it, after all!).

By extension, I’m more inclined to carefully follow the recipes of those who use a more science-led approach to recipe development and cooking, such as Heston Blumental or .

Same with baking recipes in general, which are typically dependent on specific proportions and processes.

But there are plenty of recipe developers who are solving for an entirely different problem: they’re creating recipes for the time-poor, for those catering to a family, or for those amongst us with limited energy or resources. Their mandate is to produce recipes that are straightforward and flexible rather than transcendently delicious and thus fussy.

For example, when Jamie Oliver presents me with a recipe for lasagne, I don’t believe he’s necessarily offering me the most perfected version of that dish, I believe he’s giving me a recipe that works and will taste good. And in knowing that, I have greater licence to tweak, riff and substitute.

ON TRUSTING YOUR INSTINCTS (AKA STOP PAYING ATTENTION TO RECIPE TIMINGS!!)

Here’s what I tend to follow in a recipe:

The core ingredients (e.g. fillet steak, potato etc.)

Specifications around the preparation of said ingredients (e.g. cut into 1cm cubes)

What I don’t tend to follow in a recipe (or am likely to riff on):

Timings

Peripheral ingredients (e.g. spices, herbs)

Recipe timings are very much a rough guide — and a lot of them are comically far out.

Reddit is one of the best places on the internet, both as a supremely handy, crowdsourced treasure chest of information and as a slightly unhinged corner of the internet. I recently came upon a thread about the cooking myths that most frustrated people and I can’t tell you how many times this one came up:

The point is that ovens and hobs and pans vary hugely. And ingredients vary according to their season, their age etc. That’s why developing and trusting your instincts is the only reliable way.

Sight and taste are likely to be most helpful when starting out. Evidently, it’s possible to see when something is still fresh and vibrant, or heading towards caramelised or, God forbid, burnt. As for the latter, we’ve been told this ad nauseam but I’ll repeat it because it’s true: taste. Taste constantly. And adjust.

These days, many years into my cooking journey, I rely on smell a lot, too — so much so that I rarely even set a timer anymore (who am I??).

When it comes to touch, the more you can handle your food the better. Even when you’re chopping something, you’re learning about that specific ingredient — how fresh it seems, how watery, how dense. It’s all data. Tools like mini-choppers might be convenient but they divorce you from your ingredients.

All of this to say: treat the timings of a recipe as a very rough guideline. Set a timer ahead of the suggested time and work out whether your oven seems to cook things quicker or slower than the average recipe. Pay attention to the physical indicators described in a recipe — the colours and textures to expect. Trust your instincts over the timer: you might be off initially, but over the course of months and years your instincts will be honed.

The value of making mistakes

There are no shortcuts to learning how to cook well — time and experience, and making mistakes, is everything.

I made a big mistake just last week which taught me something.

I was cooking Easter lunch and the plan was lamb shoulder. I dry brined it for a couple of days (strongly recommend) and then settled on an overnight slow-cook inspired by the respective queens of cooking, Nigella and Alison Roman.

Earlier in the week I had made lamb meatballs with fennel seeds and loved the combination. My mind was therefore fixated on the idea of lamb and aniseed. Instead of wine I slugged in a decent pour of vermouth, put the lamb in the oven and went to bed. 4 hours later I was woken up to one of the most gag-inducing cooking smells I’ve ever experienced: something about the combination of lamb fat and strong aniseed flavour was deeply, revoltingly unpleasant.

I blearily turned the oven off at 4.30am and spent an hour trying to get back to sleep (that’s how bad the smell was, and of course I was lying there worrying I had ruined 3kg of lamb shoulder!).

Fear not — the lamb ended up being DELICIOUS (once I had poured all of the offending liquid away, and refreshed it with some simple stock, ha) but I learnt a couple of valuable lessons from the experience:

Cooking something overnight when you live in a small flat is not the one. It would work if I lived in a house and there were floors between the kitchen and my bedroom, but until that day comes, I will keep my cooking to the daytime.

Aniseed as a flavour is probably better used as an accent than as a foundational base flavour.

Lessons learnt! I am now several steps closer to developing my perfect, forever recipe for lamb shoulder (and once I’ve nailed it I will share it with you!).

UNDERSTANDING YOUR PALATE (+ HOW TO SEASON)

Someone once wrote about the fact that the instruction “season to taste” was a cop-out for recipe developers.

I (respectfully) disagree.

Learning to season food to your taste is the very essence of cooking.

It goes without saying that you will know the things you tend to enjoy — specific dishes, or your favourite ingredients. And it’s likely that you might already have a sense of whether you skew sour, salty, bitter etc.

A good question to ask yourself is which cuisines you like best. Cuisines often have specific flavour leanings and if it’s a favourite of yours it will probably hold clues to your own preferences.

Very broad brush strokes but, as an example, I gravitate towards cuisines that lean more heavily on sour and bitter flavours — so Iranian food, for example, is a favourite. Meanwhile, I am less enamoured by excessive sweetness and, moving into the realm of texture, foods that are super gelatinous or excessively fatty. As a result, Chinese cuisine is one of my least favourites (I say this having travelled through China, and also as a very generalised statement). If I’m eating Chinese food I gravitate more towards Sichuan cuisine because I find the heavy use of chilli to be good at providing some cut-through.

Which cuisines do you prefer? And what does that say about your food tastes? Share in the comments if you like, I love to chat about these things!

A few thoughts on seasoning food

I believe that the average cook neglects to use salt early enough in the cooking process. I love a sprinkle of Maldon at the dinner table as much as the next person but salt’s true power lies in its ability to make other ingredients taste even more of themselves. To truly benefit from this it helps to use a higher proportion of salt earlier in the cooking process, rather than reserving most of it for the end.

Techniques like dry brining meat, or quick curing fish, or seasoning your pasta water appropriately are ways to do this.

Also important is seasoning regularly along the way — adding a little pinch of salt every time you add a new ingredient to the pan.

Typically I think of salt, bitterness and umami as the base notes in food. This is not to say that they can’t be used towards the end of cooking but I think they often have real power used earlier in the process, contributing depth of flavour upfront.

Sugar and acid, meanwhile, act as the high notes. Professional kitchens get through far more acid than the average home kitchen (read that as you wish) and towards the end of the cooking process chefs are less likely to turn to salt to give a dish its final pep, and more inclined to add vinegar, or citrus juice, or a pickled element. This lean towards acidity is one of the features that most distinguishes the professional chef from the home cook.

Acidity and sweetness — the culinary ying and yang — work particularly well together because sugar does a wonderful job of balancing out acidity without negating its sharp, tastebud-whetting effect (if you’ve been part of the Small Wins community for a while you’ll know that I’ve talked about the power of this combination before).

INGREDIENT SUBSTITUTIONS: A MATRIX

I had a search for an ingredients substitutions matrix on the internet and found all of them to be quite generic.

For example, the New York Times lumped together aubergine (eggplant), fennel and mushrooms into the category of ‘quick cooking vegetables’, but I wouldn’t substitute any of those vegetables for each other. Sure, it might technically work but it wouldn’t be the same dish — or it might turn a great recipe into something that’s merely okay.

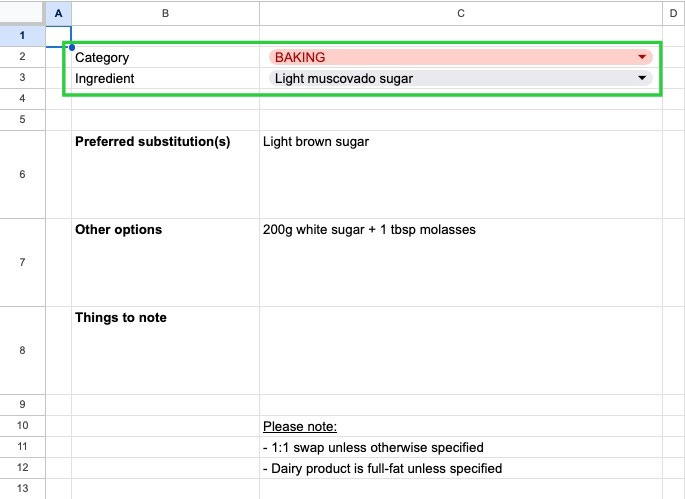

So I built my own.

This substitutions matrix is tighter/more specific — and I hope you will find it practical.

I’ve produced the information in two formats, as I know we all operate in different ways:

A simple table in a Word document, which can be printed out and inserted into your recipe book, or kept handy in the kitchen.

A Google Sheets tool where you can select an ingredient from the drop-down menus at the top (see green box below) and it’ll return my top substitution suggestion, along with some ‘second choice’ substitutions (ones that I believe may not be quite as good but would work at a push).

Here are the links: