Welcome to Small Wins, a newsletter that shares a small win with you every other week — one that has the power to improve your cooking, your home, your life. If you’ve found your way to this newsletter but are not yet subscribed, here, let me help you with that:

French fries are my weakness. If I’m eating out and they’re on the menu, I’m ordering them. And if you and I are eating out together, you better order your own portion because you won’t get a look in.

But no matter how much I love a crispy fried potato baton you will rarely catch me deep-fat frying at home: it’s a faff, it’s messy and, given the nutritional credentials, I feel that saving it for eating out makes sense.

But that doesn’t mean that you don’t get to enjoy deliciously crispy potatoes at home!!

These are the potatoes I make more than any other because: no peeling, no chopping, so easy, extremely delicious + very crispy! I challenge you not to finish them in one go.

Love,

Alexina

Coming up on Small Wins — The best way to cook courgettes is also the simplest. If you only ever learn to make one dessert in your life, let it be this one. The very best hot sauce (fermented or not).

For my Small Wins+ community — This month we did a deep-dive into the classic Victoria Sponge, including comparing the effects of different cake mixing methods and answering the question: does how much you spend on ingredients affect the end result?? Next month it’s a 101 on cooking fish from a former fishmonger (it’s me). Expect a guide on shopping for fish, the most special way to cook tuna, a super thrifty fish dish, one of the recipes that I cooked in the final of MasterChef and much more. Sign up to avoid missing out:

P.S. Becoming a paid subscriber keeps the small wins free for everyone. :)

THE SECRETS TO CRISPY

Texture, I’ve been neglecting you, I’m sorry.

I’ve been so focused on flavour (evidence 1, evidence 2) that I sort of forgot about you.

But something that I’ve been coming up against a lot recently is the realisation that most of our food preferences — in particular our dislikes — have to do with texture.

It was, in part, a question from a lovely Small Wins+ subscriber about crispy things that had me interrogating my own relationship with texture.

I hadn’t thought I was particularly fussy until I started to realise that whilst I enjoy the softness of porridge and the crunch of granola, please do not give them to me together. I am emphatically against the current, Instagram-led trend for covering breakfast items like porridge, yoghurt and overnight oats with ALL THE TOPPINGS. I just want one (maybe two) soft things with my soft porridge, it that too much to ask??

Likewise with dips: gimme houmous, gimme taramasalata, gimme baba ghanoush and give me some soft flatbreads. I don’t love my dips showered in crispy fried onions or garlic (although I can acknowledge that I’m probably in the minority here).

I do love crispy things, though — and arguably nothing crisps better than a potato.

Why?

Because of our underrated friend starch, which makes up one part of the formula for crispiness:

( FAT + STARCH + HEAT ) x SURFACE CHARACTERISTICS

Let’s break this down.

FAT will come as no surprise to anyone, given the strong association between deep fat frying and crispiness.

Fat conducts heat extremely well, making it an ideal medium for reaching the kinds of temperatures that incite crispiness and the Maillard reaction (browning) — some fats can exceed 250°C, whereas boiling water taps out at 100°C. Fat also helps to keep out moisture, since it is water-repellent.

Here are some things to consider when it comes to fat:

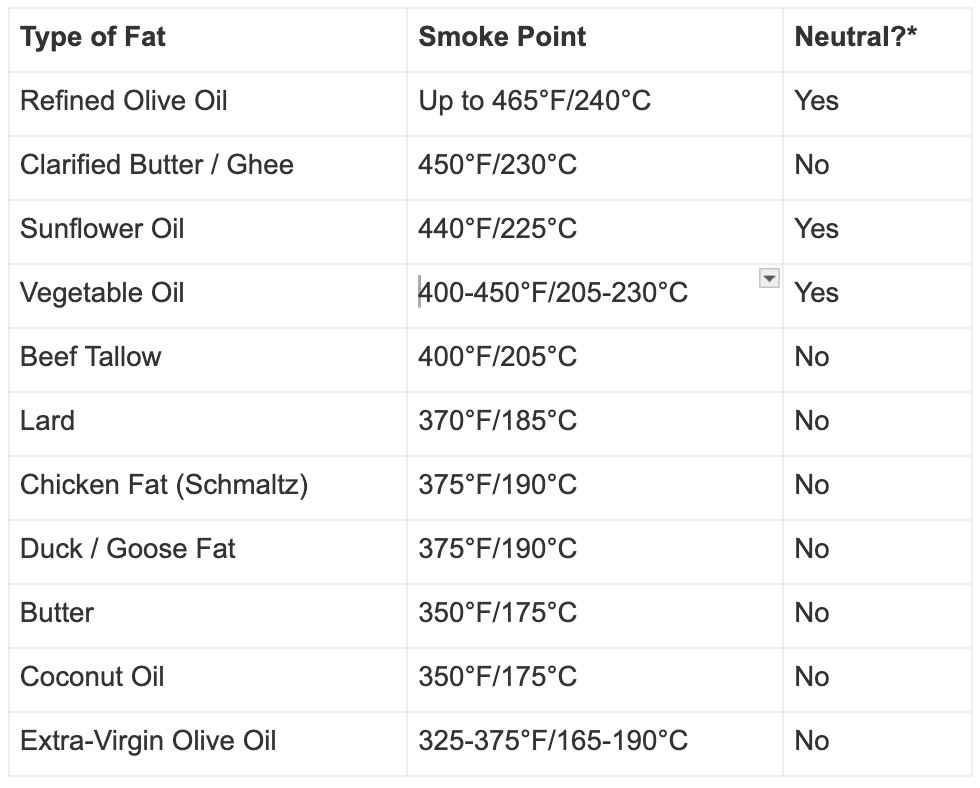

Smoke point matters — as we discovered back when we were thinking about the ultimate roast potatoes. Essentially: the higher your oil can go, the more heat can be generated and the more crispy something can get. Here’s a reminder of how different oils stack up:

Source: The Professional Chef by The Culinary Institute of America, via Serious Eats Fat also aids with crispiness through contact. Deep fat frying is effective because the food is completely surrounded, giving every nook and cranny the opportunity to brown and crisp. It’s harder to achieve all-round crispiness when pan-frying because only part of the food will be in contact with the surface at any given time and, at a microscopic level, the surface of a pan is highly uneven. Two things can help:

1/ Using sufficient oil (when pan-frying) to help mitigate the uneven surface

2/ Weighing the item down to enforce more contact (if you regularly cook things at high heat on the hob e.g. steak, then a chef’s press could be a worthwhile buy)

STARCH goes largely under the radar in the kitchen, overshadowed by the big character that is flour (which, yes, does contain starch but also other things). This is a shame because texturally-speaking starch is a secret weapon: able to both make food more silky, more tender (see ‘the Chinese restaurant secret to tender meat’) — or conversely lighter and crisper.

How can it do both of these things?

It simply depends how you treat it. Up to a certain temperature starch molecules will absorb water (“gelatinisation”) and this is what leads to silky and/or tender textures. But if you subsequently drive that water off through high-temperature cooking what’s left behind is a brittle web of starch molecules that reads as crispy.

Potatoes are inherently starchy which is why they achieve crispness quite easily (and if you’ve been part of the Small Wins community for a while you’ll know that we stan potato starch around here). But for non-starchy ingredients (e.g. proteins like chicken and fish) you can dust these in seasoned flour, toss them in a cornflour slurry, add a breadcrumb coating or cover in a batter to provide some of that starch.

When it comes to using batters in deep-fat frying, the mix will contain standard flour (starch + protein) but there are ways to further enhance the crispiness:

Replace up to 50% of the flour (by volume) with cornflour or potato starch to up the overall starch content (as in the ethereally light tempura)

Use vodka to inhibit the formation of gluten, which would otherwise make the batter slightly tougher

Use carbonated liquids such as sparkling water or beer to contribute extra air to the party: the air bubbles expand as they hit the hot oil and then set, creating a lighter, crispier texture

HEAT is — as you might have guessed by now — the most essential!

Perhaps the main challenge with crispy foods is balancing cooking the interiors with achieving a perfectly golden exterior. You need the centre of the food to be cooked through without over-browning the outside. You also need to drive off a certain amount of the moisture in the food without completely drying it out (you wouldn’t want the flesh of your fried chicken to be dry, would you??). For that reason, I can’t emphasise the following enough:

It’s best to think of cooking and crisping as completely separate steps.

We do this already with roast potatoes: we par-boil them to cook them through, then we pop them in a hot oven with lots of fat to get that crunchy, crispy exterior. This is also the idea at the heart of double- and triple-cooked chips.

Unless what you’re frying cooks really quickly (e.g. sage leaves) your standard process should be to cook at a lower temperature first (around 150 to 160°C/300°F to 320°F), and then finish off at a higher temperature (around 180 to 190°C/355°F to 375°F) to get the outside perfectly crisp and golden.

As much as this represents an extra step, it actually makes your life easier:

It gives you the chance to prep in advance. Let’s say you’re making fried chicken for your mates: you can do the initial fry up to 3 days in advance (store in the fridge) and do the second, higher-temp, much quicker fry when they arrive.

It’s less stressful to fry things when you have a singular aim: when it comes to the second fry all you need to worry about is getting the colour that you want — which couldn’t be easier!

The above can also be applied to oven cooking (e.g. a roast chicken: cook it initially at a lower, gentler temperature then give it a quick blast at the end to crisp up the skin).

When it comes to pan-frying, you must also consider where the intensity of the heat is coming from: so if you’re cooking a piece of fish and want to achieve crispy skin, the trick is to cook it 3/4 of the way through skin-side down (i.e. in contact with the hot pan).

Finally, tied to heat is, of course, dehydration!

The enemy of crispness is moisture, yes, but that doesn’t mean that what you fry has to be bone dry (though obviously it can’t be sodden). To a certain extent the application of high heat will drive off a decent proportion of that moisture but it never hurts to help things along: if you’re not going down the slurry/breadcrumbing/batter route, dab ingredients dry with kitchen towel prior to attempting to crisp them — or allow parboiled potatoes to stream-dry before proceeding to the oven-roasting stage.

A tip for the best crispy fried garlic

Speaking of double-cooking, this is one I learnt whilst working at a restaurant: for delicious fried garlic that is not bitter, poach the slices in milk first and pat throughly dry before deep-frying them!

Finally, SURFACE CHARACTERISTICS!

Quite simply: the greater the surface area of the thing that you want to crisp up — and the more of that surface that is in contact with the source of heat — the more potential for texture.

Two ways to influence this:

How you prepare and cut your ingredients:

Thinly-sliced crisps will be crispier than French fries, which will be crispier than thick-cut chips etc. etc.

In the case of the recipe included further below, smashing the potatoes flat against the baking tray is helping maximise the area in contact with the hottest element. Likewise, bashing out a chicken breast flat for schnitzel not only helps it cook evenly, but increases the breadcrumbed surface area as well as how much of it ends up in contact with the pan.

Roughing up the exterior!

For inherently starchy ingredients like potatoes and cassava, consider adding a touch of bicarbonate of soda to the boiling water to turn it slightly alkaline — this will help the exteriors break down. Giving them a good shake once they’ve been drained enables you to double down on the mush. Mushy exteriors = extra crispness.

When adding a coating, consider your crumb of choice: Panko breadcrumbs with their big craggy flakes will offer a crunchier experience than fine breadcrumbs (crisps and cornflakes can make great crispy coatings too).

THE EASIEST, CRISPIEST POTATOES

Serves 2 to 4 (honestly amazed at how many potatoes I can eat when they’re made like this)

Ingredients

1kg Vivaldi salad potatoes (available at Sainsbury’s) — you can use any variety of salad potato obviously (!) but these are particularly delicious

1.5 litres water

2 tbsp Diamond kosher salt (or 1 tbsp fine sea salt)

Generous 1/4 cup olive oil (I use EVOO)

1/2 to 3/4 tsp flaky sea salt, to taste

Equipment

1 to 2 large baking trays

Method

Add the potatoes to a large saucepan then cover with cold water and salt. Replace the lid and bring the water to a simmer. Allow the potatoes to bubble away until tender, around 15 minutes (the timing can vary depending on type of potato, how old they are etc.). To test the potatoes, insert a sharp knife into one and if it slides readily off the knife then they’re ready.

Preheat the oven to 220°C/200°C fan/425°F/gas mark 7.

Drain the potatoes and let them steam-dry for 10 minutes before transferring to one or two large baking trays (make sure there’s plenty of space). Using a flat-bottomed glass, crush each potato until it’s starting to splay out.

I’ve seen a lot of people do this by placing another tray on top of the potatoes and flattening them way. I would rather wash up a glass than a tray, not to mention you have less control

If you crush the potatoes too thin it’ll be hard to get off the baking tray later — somewhere in the middle is good

Drizzle over the olive oil and sprinkle over the flaky sea salt to taste. Transfer to the oven and bake until golden and crispy, around 30 to 40 minutes. Serve immediately!

Super article on crispy potatoes,Alexina, with lots of tips